Introduction

The concept of protection has its origins in international law. Humanitarian actors first defined it, then advocated and supported the United Nations (UN) Security Council and other peace and security organisations to progressively adopt a similar approach, in order to ensure the protection of civilians (PoC) in armed conflict.

Each organisation that contributes to civilian protection naturally tailors its approach to a specific context, mandate, objectives, normative references or principles of work. While humanitarian actors seek to maintain distinct roles from political or military actors, some are also keen to distinguish protection concepts, generally opposing 'humanitarian' or 'rights-based' protection to the protection of civilians by peace and security operations.

This paper provides an overview of the main perspectives on the protection of civilians in armed conflict and aims to promote a shared understanding of the concept, while recognizing the conceptual discrepancies as well as specificities inherent to each protection actor.

Protection norms and applicable legal frameworks

In situations of armed conflict, the 1949 Geneva Conventions and their 1977 Additional Protocols [1] are the 'core' [2] of international humanitarian law (IHL) and contain specific rules to protect civilians. The fourth and historically the last Convention [3] is dedicated to the protection of civilians.

Other bodies of international law, notably international human rights law (IHRL) and national law, continue to apply in armed conflicts. In situations where the levels of violence do not amount to an armed conflict, notably during internal disturbances that have not reached the level of violence characteristic of a non-international armed conflict [4], civilians are still protected by IHRL and national law. It should be noted that some but not all provisions of IHRL can be derogated from (i.e. suspended) in situations of armed conflict and in peacetime, for example during a state of emergency.

Civilians seeking safety from conflict or persecution outside of their country of origin are protected by the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, also known as international refugee law (IRL). The original document inspired a number of regional instruments. [5] In recent years, with the increase of mixed migration flows, for example due to the effects of climate change, efforts have been made by the international community to further define the obligations of States toward civilians on the move through the 2016 New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants and the resulting 2018 Global Compacts for Safe and Orderly Migration [6] and Refugees. [7]

Individuals forcibly displaced within their country of residence fall under the protection of the 1998 UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement. A non-binding normative framework derived from existing treaty-based and customary law [8], these Principles apply in situations of internal displacement as a result of conflict, persecution, natural disasters or development projects. They have also inspired States at the regional or national level to adopt legal instruments or policies to protect the internally displaced persons (IDP). [9]

Finally, and as described below, civilians are further protected by normative frameworks such as the UN Charter or UN Security Council resolutions.

Protecting civilians is a primary responsibility of State authorities and parties to a conflict, supported by other protection actors [10]

State authorities bear the primary responsibility to protect civilians within their borders. [11] In situations of armed conflict, those forces or groups who control a given territory - including inter alia occupying forces, organised armed groups and in some cases international peace and security forces - are legally bound to ensure the protection of civilian populations in areas they control, including by taking all measures to spare them from the effects of hostilities.

Some States have developed dedicated laws, policies and strategies to ensure or contribute to the protection of civilians, within their territory or abroad. For example, the UK Government adopted a PoC strategy in 2010 [12], and the Uruguay Government published a policy on protection of children in peace operations in 2020 [13].

Beyond States and non-State parties to a conflict, which hold an obligation to protect civilians, a variety of non-state actors, including humanitarian and other civil society organisations, the media, or civilian communities themselves, may have a mandated role or an interest in protecting civilians from actual or potential violations of international law. Such protection actors can also contribute to eradicating the causes or the circumstances that lead to failures to protect - including by addressing authorities and other actors responsible for the violations, or those who may have influence over them.

The humanitarian protection approach

Faced with multiple approaches to the concept of protection, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) convened, from 1996 to 1999, a series of workshops with the main human rights and humanitarian actors. In 1999, they agreed to define protection as:

“all activities aimed at obtaining full respect for the rights of the individual in accordance with the letter and the spirit of the relevant bodies of law (i.e. International Human Rights Law (IHRL), International Humanitarian Law (IHL), International Refugee Law (IRL)).”

This definition was endorsed by the humanitarian Inter Agency Standing Committee (IASC) in December 1999, which also issued a Policy on Protection in Humanitarian Action in 2016. [14] Over the years, the IASC has attempted to place protection at the centre of humanitarian action, alongside assistance.

As "violations of international [...] law may be amongst the principal causes and consequences of humanitarian crises", [15] protection activities aim to complement humanitarian assistance with "efforts to prevent and respond to violations of international law". In practice, humanitarian actors are required to ensure the protection of civilians in all types of humanitarian crises, including in situations of armed conflict [16] under which civilians face increased threats of violations of their basic rights.

Protection action also informs all aspects of a humanitarian response, as it provides standards and principles to 'do no harm' and to safeguard the security, safety, well-being and dignity of beneficiaries while providing assistance.

Humanitarian actors have distinct protection mandates. While some organisations are specifically mandated as having special obligations toward categories of individuals (e.g. ICRC for civilians affected by armed conflict as well as detainees, wounded, sick or shipwrecked combatants; UNHCR for refugees, IOM for internally displaced people; UNICEF for children, etc.), other organizations may simply choose to focus on protecting one or more specific categories of civilians at risk.

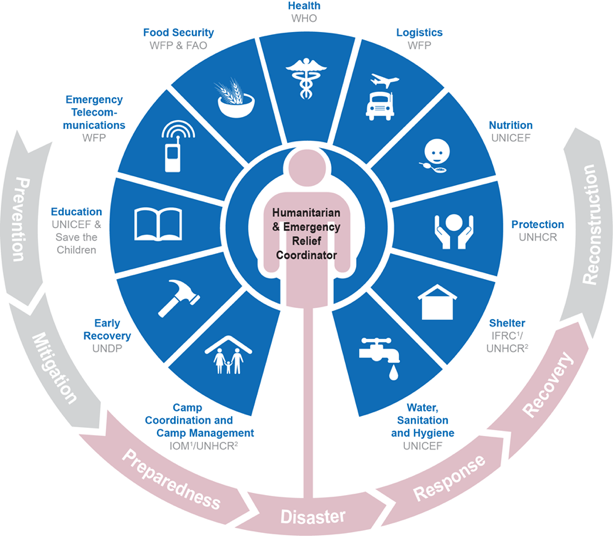

At the global level, humanitarian actors ensure coordinated humanitarian protection mainstreaming, integration and response under the overall guidance of the IASC (particularly, the IASC Policy on Protection in Humanitarian Action) as well as through a dedicated coordination mechanism: the Global Protection Cluster (GPC) , led by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

Figure 2: Humanitarian Cluster Approach (IASC)[17]

At the regional or national-level, the Humanitarian Coordinators (HC) and the Humanitarian Country Teams (HCT) have strategic or operational responsibilities on protection (described in the IASC Policy). They are supported by Protection Clusters, technical-level groups of professionals from United Nations agencies, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), other international organizations or national/local authorities engaged in protection work in humanitarian crises. The Global Protection Cluster include four specialized Areas of Responsibility, often coordinated by sub-clusters on Child Protection (focal point: UNICEF), Gender-Based Violence (focal point: UNFPA), Housing, Land and Property (focal point: NRC) and Mine Action (focal point: UNMAS).

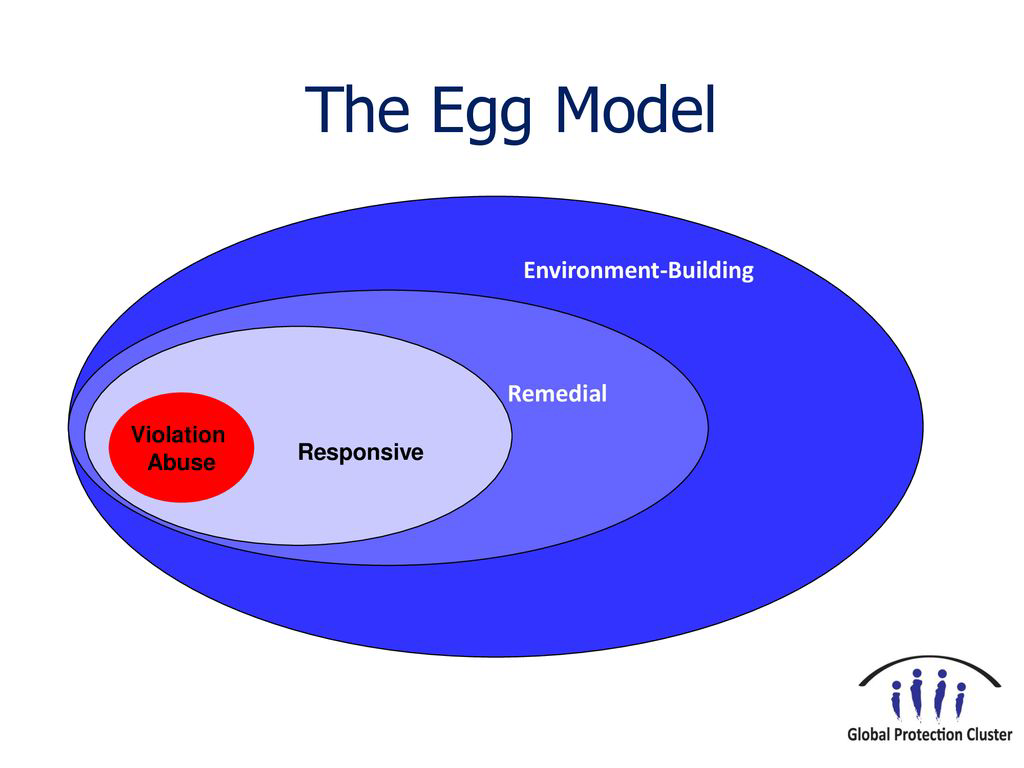

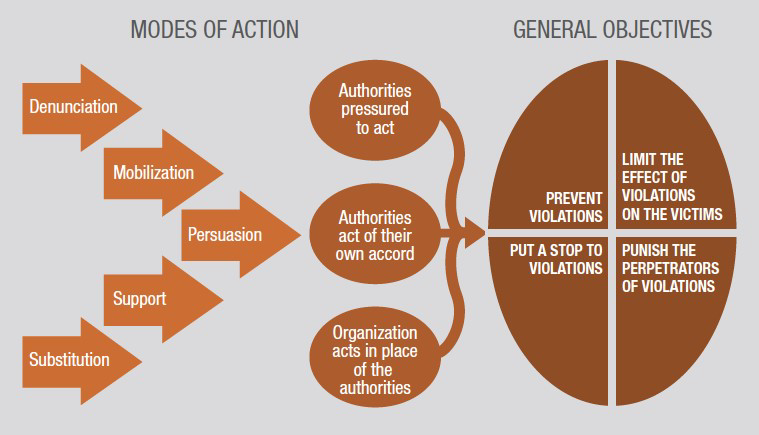

Humanitarian actors follow common [18] and organisation-specific [19] policies and protection principles or standards [20], consistent with the principles of humanitarian action. Their actions are generally presented under three levels of intervention and and four modes of action, presented in the figures 3 and 4 below.

Figure 3: Protection Egg Model (See: the Global Protection Cluster website)

In Figure 3, note the meanings of each term:

- Responsive action: stop, prevent and alleviate the effects of the threat,

- Remedial action: restore people’s dignity and ensure adequate living conditions following the pattern of abuse,

- Environment building action: build a social, cultural and legal environment conducive to the respect for the rights of the individual.

Figure 4: Four modes of protection action

(See Enhancing Protection for civilians in armed conflict and other situations of violence, ICRC, Novembre 2012)

Convergence and distinction between humanitarian protection and protection of civilians in armed conflict

Protecting civilians caught up in war is one of the core objectives of the UN, inscribed in its founding Charter. Following the Rwandan genocide and civilian massacres in former Yugoslavia in the 1990s, the UN Security Council has progressively recognized the protection of civilians as a core consideration of modern armed conflict. From 1999 onward, it has held regular meetings and issued multiple resolutions and presidential statements on the general issue of the protection of civilians in armed conflict, and also in favour of categories of population with specific needs, starting with 'children and armed conflict' [21], as well as 'women, peace and security' [22]. More recently, the Security Council also issued dedicated resolutions in favour of other categories of individuals at risk in situations of armed conflict, such as journalists, humanitarian actors, missing persons or individuals with disabilities.

Supported by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA), on behalf of the humanitarian community, to develop its approach on the protection of civilians in armed conflict [23], the UN Security Council also uses the IASC definition. The building blocks of the Security Council's PoC agenda cover a wide spectrum of activities which extend beyond humanitarian action, as they also include political, security or judicial action to ensure civilian protection.

The five building blocks of the UN Security Council's PoC approach:

- "enhancing compliance with applicable international law and relevant Security Council decisions in the conduct of hostilities,

- facilitating access to humanitarian assistance,

- protecting forcibly displaced persons, women and children,

- providing protection through UN peace operations and,

- responding to violations through targeted measures and the promotion of accountability. " [24]

Related to the above list, one key measure has been the UN Security Council assigning mandates to protect civilians to UN peacekeeping operations from 1999, including an authorization to use force to protect civilians under threat of physical violence. While 'PoC' is often referred to as limited to the [25] 'PoC mandates' assigned to UN peacekeeping operations, the UN Security Council has also used other vehicles to protect civilians, such as 'sanction regimes' [26], human rights monitoring and reporting processes [27], or criminal investigations and accountability (for instance through international or hybrid courts). It is currently also considering enhancing the use of preventive diplomacy and political Missions to enhance the protection of civilians agenda. [28]

Humanitarian protection's scope of action

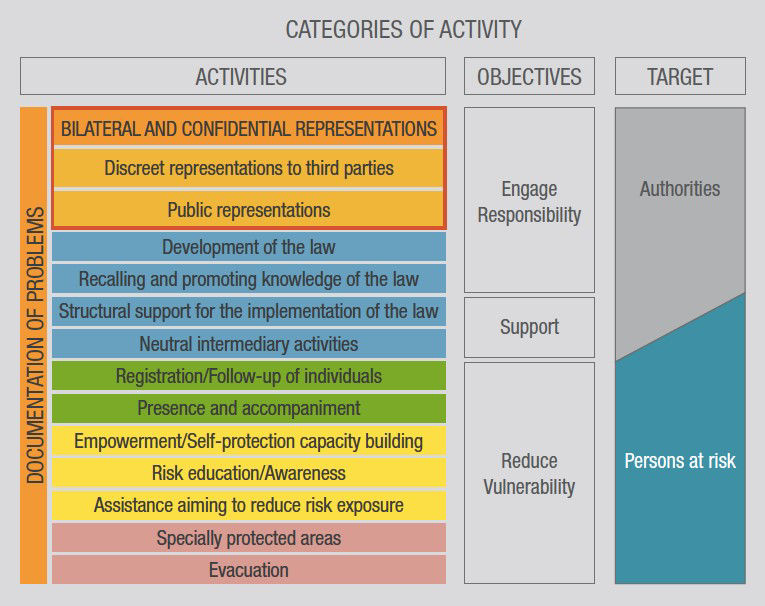

While they share the same overall objective and definition for the protection of civilians, humanitarian actors can seek to share and coordinate or distinguish some specific protection activities, generally with a view to safeguarding the neutrality of humanitarian action, as well as ensuring the protection of sources, witnesses or victims. Humanitarians generally focus their protection activities on engaging the responsibility of duty-bearers and/or reducing the vulnerabilities of persons at risk - see example in the Figure below.

Figure 5: Example - ICRC categories of humanitarian protection activities

(Source: Enhancing protection for civilians in armed conflict and other situations of violence, Chapter 2, ICRC, November 2012)

Perspectives and discrepancies on the definition and scope of the protection of civilians concept

Despite the conceptual convergence and common definitions presented above, reasons why some actors distinguish 'humanitarian protection' from 'protection of civilians', include:

- the protection of civilians mandated task assigned to UN peacekeeping Missions is often - and falsely [29] - perceived as limited to the authority these Missions receive from the Security Council, under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, to use force to protect civilians under (imminent) threat of physical violence;

- to safeguard the principle of neutrality of humanitarian action and explicitly distinguish the roles of humanitarian protection actors from those invested with security and/or political mandates, such as UN peace operations.

In addition, the scope of the protection of civilians concept can vary slightly from one organisation to another. It is sometimes applied in situations that fall outside of the strict purview of the IASC definition. For instance:

- in armed conflict, the protection concept applies to civilians (as defined by article 4 of the third Geneva Convention of 1949), as well as to other categories of individuals protected under the first three Geneva Conventions (e.g. sick, wounded or shipwrecked combatants); [30]

- some organisations embrace not only the protection of individuals, but also the protection of civilian objects under the same concept (e.g. schools, hospitals, water treatment plants, political and judicial buildings, crops and livestock, etc.) - for more details, see the Expert note on the concept of Civilian;

- minimizing collateral damage resulting from military operations is a protection activity which can apply to situations considered legal under international law, insofar as it complies with the IHL principles of military necessity, precaution and proportionality [31];

- some instances of violence affecting civilians are not yet deemed violations of international law, due to the lack of existing legal standards or norms. For instance, gaps in legislation on the use of explosive weapons [32] in urban or populated areas [33], which often lead to devastating harm to civilians [34], may result from the use of new and unregulated weaponry;

- protection mandates and strategies can also aim to address specific types of violence affecting civilians, but not deemed violations of international law. AMISOM, the AU Mission in Somalia, has for instance adressed car accidents as a protection risk under its casualty tracking mechanism and PoC strategy [35]

Despite the above-mentioned multiplicity of perspectives or conceptual discrepancies, the author of this note supports the inclusive approach adopted by the ICRC. As the first international humanitarian organisation mandated to protect victims of war [36], the ICRC has been at the forefront of the conceptual and policy developments on protection. It uses "in its internal and external communication, [...] the expression protection of the civilian population although the literal definitions of these terms do not reflect the full scope of protection activities". [37]

Protection of civilians by peace and security operations

International or regional peace and security forces are bound by the existing applicable legal frameworks - IHL in situations of armed conflict, IHRL at all times - to safeguard civilians from the negative effects that may arise from their own military and/or police operations. They are also bound to promote compliance by security actors they conduct joint operations with or provide support to. This principle has for instance led the UN to regulate its support provided to non-UN security forces under the Human Rights Due Diligence Policy (HRDDP). [38]

Beyond these core obligations applicable to international security actors, most large UN Missions are mandated to protect civiliams from harm caused by other actors. And while it is not generally explicitly part of their mandates, African Union, EU or NATO operations, for instance, are also increasingly taking the protection of civilians from external harm into account, including through their respective concepts and strategies.

Peace and security organs under the UN, AU, EU, or NATO have developed policies, guidelines, military concepts or strategies on the protection of civilians, tailored to their specific mandates and operations and generally focus their approaches to addressing threats of physical violence and other conflict-related violations, such as grave violations against children or conflict-related sexual violence.

The UN Department of Peace Operations (UNDPO) [39] was for instance the first of the above-mentioned institutions to issue its 'PoC concept' in 2009, followed by a PoC Policy [40] and Military Guidelines in 2015, PoC Police Guidelines in 2017 and a PoC Handbook in 2020. They provide the operational standards and guidance for PoC objectives and activities, placed under three tiers of action: 1. protection through dialogue and engagement, 2. provision of physical protection, 3. establishment of a protective environment. Peacekeeping operations with a PoC mandate are now all required to develop a PoC strategy tailored to their specific mandate and context.

The 4-tiered African Union approach (political action, security action, judicial action, environment building action), inspired by the UNDPO PoC model, is enshrined in the Draft Guidelines for the Protection of Civilians in AU Peace Support Operations of 2012. It guided the development of mission specific protection of civilians strategies by AMISOM (AU Mission in Somalia) [41], the MNJTF (Multi-national Joint Task Force of the Lake Chad basin) [42], or the G5 Sahel countries [43].

NATO has also issued a PoC policy in 2016 [44], later complemented by a PoC Military Concept (2018) [45] and Handbook (2018) [46] which proposes a conceptual framework with three lines of effort: 1. Mitigate harm from perpetrators of violence, 2. Facilitate access to basic needs and 3. Contribute to a safe and secure environment.

Depending on their mandate and capabilities, which are generally broader in the case of multi-dimensional UN or AU operations, these peace and/or security operations can contribute to the protection of civilians through a wide range of political, security or environment building actions. These include, inter alia : engagement and dialogue or the provision of good offices, public communication and advocacy, governance, police and military operations, justice and the rule of law, security sector reform (SSR), demobilisation, disarmament and reintegration (DDR), human rights protection and promotion, mine action, support to humanitarian access or to the return of IDP and refugees. The UN Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs recognizes for instance the contribution of Special Political Missions to the protection of civilians [47] through the above-mentioned activities (except the use of force to protect civilians, as they are not mandated or provided with police or military capabilities to carry out such a task).

While UN or AU peace operations generally include a PoC advisor unit as well as a human rights teams [48], and in spite of the guidance development efforts mentioned above, an operation's ability to address compliance and protect civilians is often limited by its primary focus on political objectives and its own security. For example, despite some successes, and notwithstanding other challenges facing UN or AU peacekeeping operations, these competing interests and goals lead to regular failures to protect by peacekeepeking operations. Preventing or swiftly reacting to attacks against civilians, is expected of those operations. As well as addressing the inability of some host government institutions to protect civilians, or acknowledging a host State's predatory behaviour, when applicable. However, some or all of these activities may result in security risks for blue or green helmets, or hamper political relations with national authorities, if implemented inadequately. This dynamic also undermines the varying and often weak compliance to the HRDDP across UN peace operations, and further complicates the ability of peacekeeping operations to effectively address and support national authorities to protect civilians.

Conclusion

Humanitarians have progressively harmonized their approach to the protection of civilian victims in both natural disasters and conflict environments and greatly contributed to the mainstreaming of protection of civilians approaches across peace and security actors. Many however recognize that more could be done to ensure the centrality of protection in humanitarian action. The ongoing review of the implementation of the IASC policy should assist in identifying and addressing some of these challenges.

The protection of civilians approaches presented above promote and respect the primary responsibility for State authorities to protect civilians at risk. PoC action should however be strictly distinguished from the concepts of 'humanitarian interventions' (understood as the use of force against a State in order to protect its own population) and the 'responsibility to protect' (R2P), as these concepts sometimes entail taking action against the sovereignty of a State [49].

Footnotes

- [1] The Geneva Conventions, in particular Common Article III, apply universally in armed conflicts. The applicability of the Additional Protocols depends on various factors, e.g. whether a conflict is international or non-international in nature and whether a State is a party to a particular Protocol.

- [2] Provisions included in the 1998 Statute of the International Criminal Court or other international treaties which prohibit the use of certain weapons and military tactics, and protect certain categories of person and object from the effects of hostilities, are now thought to reflect customary IHL. See https://www.icrc.org/en/download/file/4541/what-is-ihl-factsheet.pdf

- [3] The development of the fourth Geneva Convention was initiated in the 1920s, following the First World War. It was however only finalized and adopted in 1949.

- [4] The ICRC proposes the following definitions: "International armed conflicts exist whenever there is resort to armed force between two or more States. Non-international armed conflicts are protracted armed confrontations occurring between governmental armed forces and the forces of one or more armed groups, or between such groups arising on the territory of a State [party to the Geneva Conventions]. The armed confrontation must reach a minimum level of intensity and the parties involved in the conflict must show a minimum of organisation." For further details, see https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/assets/files/other/opinion-paper-armed-conflict.pdf and https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/resources/documents/interview/2012/12-10-niac-non-international-armed-conflict.htm

- [5] Such as the 1969 Africa Refugee Convention, the 1984 Latin American Cartagena Declaration and the Common European Asylum System (CEAS). See https://reliefweb.int/report/world/1951-refugee-convention-70-years-life-saving-protection-enar

- [6] https://www.iom.int/global-compact-migration

- [7] https://www.unhcr.org/the-global-compact-on-refugees.html

- [8] Specifically: IHRL, IHL and refugee law.

- [9] Such as the 2009 Kampala Convention for the African continent; in Chad, the 2017 revised version of the Penal Code, which has incorporated the war crime of forced internal displacement; in Niger, the 2018 law on the protection of and assistance to IDPs; or policies and plans to work on durable solutions for IDPs in CAR, Nigeria, Somalia and Sudan

- [10] For further details on the Protection architecture, see Chapter 3 of the Professional Standards for Protection work, ICRC, 218. See https://www.icrc.org/en/publication/0999-professional-standards-protection-work-carried-out-humanitarian-and-human-rights

- [11] The 3-tiers of IHRL protection/state responsibilities include: prevent, end and redress.

- [12] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/32950/ukstrategy-protect-cvilians-arms-conflict.pdf

- [13] https://www.keepingchildrensafe.global/blog/2020/02/27/uruguays-military-leads-on-child-safeguarding/

- [14] See Protection of Internally Displaced Persons, Inter Agency Standing Committee Policy Paper, December 1999 and https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/iasc-protection-priority-global-protection-cluster/iasc-policy-protection-humanitarian-action-2016

- [15] The Centrality of Protection in Humanitarian Action, Inter Agency Standing Committee Policy Paper, December 2013.

- [16] I.e. international and non-international armed conflicts, or other situations of violence, as defined in the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949 and their two Additional Protocols of 1977.

- [17] See https://www.globalprotectioncluster.org and the chart at: https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/coordination/clusters/what-cluster-approach

- [18] Policy on protection in humanitarian action, Inter Agency Standing Committee Policy, October 2016.

- [19] For example, see the ICRC Protection Policy, ICRC, September 2008.

- [20] Professional standards for Protection work, ICRC, 2018 (https://www.icrc.org/en/publication/0999-professional-standards-protection-work-carried-out-humanitarian-and-human-rights) or the Sphere Handbook, Protection Principles, pp.32-48, Sphere Project, 2018. For more details, see https://www.globalprotectioncluster.org

- [21] https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/children-and-armed-conflict/

- [22] https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/women-peace-and-security/

- [23] OCHA drafts UN Secretary General Reports on PoC, including its Informal Expert Group on PoC.

- [24] Building a Culture of Protection: 20 years of Security Council engagement on the Protection of Civilians, OCHA Occasional Policy Paper, May 2019.

- [25] See further details in the following section on 'perspectives and discrepancies'.

- [26] https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/repertoire/sanctions-and-other-committees

- [27] In 2005, UNSCR 1612 of 2005 has for instance identified six grave violations against children in conflict (killing and maiming, recruitment and use of children as soldiers, abduction, rape and sexual violence, attacks against schools and hospitals, denial of humanitarian access) for which the Council requested the establishment of a dedicated monitoring and reporting mechanism (MRM). In 2010, UNSCR 1960 further requested the Secretary-General to establish the monitoring, analysis and reporting arrangements (MARA) on conflict-related sexual violence.

- [28] See https://www.ipinst.org/2021/07/un-special-political-missions-and-protection-a-principled-approach-for-research-and-policymaking

- [29] As clarified by the UN Security Council in 2013 through its resolution 2086 on UN peacekeeping (para. 8): the PoC mandate for peacekeeping operations implies to "protect civilians, particularly those under imminent threat of physical violence". Indeed, while language varies slightly between country-specific Security Council resolutions, all of them distinguish the establishment of the PoC mandate from the specific authorization to use force to protect civilians under threat of physical violence. The latter authorization thus embodies only part of the PoC mandated task.

- [30] Including combatants no longer taking part to hostilities. See Enhancing protection for civilians in armed conflict and other situations of violence, ICRC, November 2012.

- [31] https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/customary-ihl/eng/docs/v2_rul_rule14

- [32] Explosive weapons include for instance artillery, mortars, air-delivered general purpose bombs, rockets and multiple launch rocket systems.

- [33] https://www.iihl.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Weapons-and-international-rule-of-law_Sanremo-Round-Table-2016-3.pdf

- [34] https://www.icrc.org/en/document/explosive-weapons-in-urban-area

- [35] Car accidents have sometimes been included in protection of civilians strategies, as their occurrence can negatively impact the image of an organisation. For instance, AMISOM's (the AU Mission in Somalia) Protection of Civilians strategy has addressed multiple instances of civilian harm resulting from inadequate driving by some troops within its ranks.

- [36] The ICRC was founded in 1863.

- [37] Enhancing protection for civilians in armed conflict and other situations of violence, ICRC, November 2012.

- [38] See https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/Inter-Agency-HRDDP-Guidance-Note-2015.pdf

- [39] Formerly known as the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations or DPKO. See https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/department-of-peace-operations

- [40] The initial versions of the DPO Policy for the Protection of Civilians in UN peacekeeping (2015) and of the Handbook on The Protection of Civilians in UN Peacekeeping(2020) were drafted by the author of this note.

- [41] https://www.accord.org.za/news/tfpaccord-conduct-amisom-protection-civilians-strategy-implementation-workshop/

- [42] The MNJTF PoC strategy was drafted in 2017, with the support of UNOCHA and the author of this note.

- [43] The G5 Sahel PoC strategy development process was initiated by the G5 Sahel Permanent Secretariat early 2020, with the support of OHCHR. See https://www.g5sahel.org/g5-sahel-diagnostic-et-consultation-pour-lelaboration-dune-strategie-regionale-de-protection-des-civils/

- [44] https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_133945.htm

- [45] https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_135998.htm

- [46] https://shape.nato.int/resources/3/website/ACO-Protection-of-Civilians-Handbook.pdf

- [47] https://www.unocha.org/sites/unocha/files/20210517%20Concept%20note%20for%20sharing%20-%20SPM%20contributions%20to%20protection%20of%20civilians.pdf

- [48] Special political Missions and large AU forces also contain a protection of civilians/human rights team.

- [49] For instance, as explained in the DPO Policy for the protection of civilians, "the responsibility to protect (R2P) also aims at addressing instances of physical violence, with a specific focus on mass atrocities (genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing). While the R2P framework shares some legal and conceptual foundations and employs some common terminology with PoC, they are distinct. Most importantly, R2P may be invoked without the consent of the host state, specifically when the host state is failing to protect its population. R2P thus envisages a range of action that goes beyond the principles of peacekeeping, which require the consent of the host state".

---

Baptiste Martin is Course Director of "Protection of Civilians, from Humanitarian to Peace Operations" at the Geneva Centre of Humanitarian Studies. He has 20 years of experience in conflict and post-conflict contexts, including in Israel/Palestine, Iraq, Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Central African Republic (CAR) and the G5 Sahel region.